Mosses, Liverworts, & Hornworts of the World: A Guide to Every Order

Joanna Wilbraham

Princeton University Press

Published August 2025

ISBN 9780691265193

Described as a magnificently illustrated guide to the bryophyte species found across the world, Mosses, Liverworts, & Hornworts of the World certainly lives up to its billing. For anyone wanting to get to know this often over-looked and under-appreciated group of plants, the book provides an excellent overview, showcasing their diversity, interesting biology and miniscule beauty. The focus on selected genera and species enables breadth and depth without becoming overwhelming. Author Joanna Wilbraham is Principal Curator at the National History Museum and her expert knowledge is clearly conveyed, with all specialist terms defined and included in a glossary.

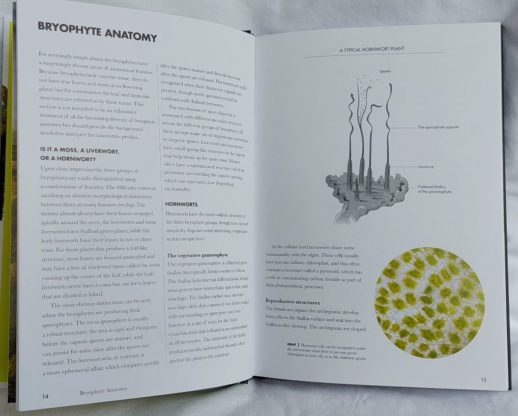

The guide starts with an introduction to the estimated 20,000 species of bryophytes (plants that reproduce by spores rather than seeds) and their evolution over 473 million years since plants first made the transition to life on land. The height of bryophytes is limited by their lack of vascular tissue (xylem and phloem) but this has not hindered their ability to thrive in diverse environments. The general and distinct anatomical features of mosses, liverworts and hornworts are explained with the help of diagrams. Passing reference is made to their symbiotic relationships with fungi, in common with many plants, and also with cyanobacteria, which I am intrigued to learn more about.

For a supposedly ‘simple’ plant, the bryophyte life cycle is surprisingly complicated. Spores germinate into filaments from which leafy plants develop, which produce male and/or female gametes. Fertilisation initiates the formation of the spore-producing structure, normally a stalk with a capsule at the top. Various strategies are used to expel or otherwise distribute the spores from the capsule. For many species, however, sexual reproduction is not essential (for one species of liverwort it is not even possible, with male and female plants separated by the Atlantic Ocean!) and bryophytes use various means of vegetative, clonal reproduction.

The history of bryophyte classification is summarised, including issues arising from the same species being assigned different names in different places, along with the important role of DNA analysis in current taxonomy. Phylogenetic trees illustrate the complexity of the task. Our impact on bryophyte habitats and distribution, and the need to gather more data and take action to preserve diversity are emphasised.

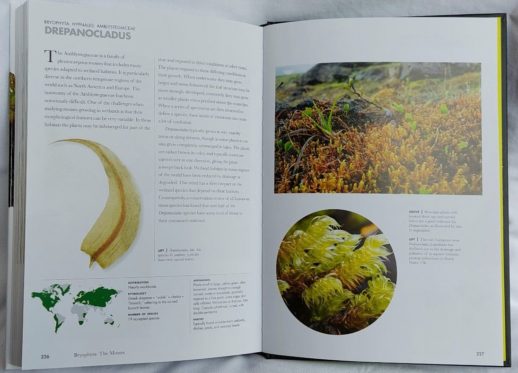

The main body of the book is divided into sections on the hornworts, liverworts and mosses, with a single or double-page spread devoted to one or more genera from every order. These genus profiles include a box with a distribution map, etymology, number of species, appearance and habitat. The accompanying text and photographs of particular species within the genus highlight characteristic and interesting features.

From these I learned, for example, that Conocephalum liverworts smell strongly of turpentine when crushed, Colura trap microscopic animals within water sacs (it’s still to be established if they’re actually carnivorous), Radula liverworts produce compounds with cannabinoid-like activity, and a species of Plagiochila that is used for healing wounds in traditional Indian medicine has been shown to promote the growth of blood vessels in lab tests.

To ensure proximity for fertilisation in Leucobryum mosses, the tiny male plants grow on the leaves of the female plants. Physcomitrium patens is used as a model species for research around the world, with all lab cultures arising from a single spore collected in Huntingdon in 1962. Hypnum mosses were so named after their use as a stuffing for pillows, and the adaptations of shade-loving Schistostega to low light levels make it appear luminous. A micrograph of Sphagnum reveals how its cellular structure enables it to hold so much water.

The distribution maps show how some bryophytes are found across the world while others are intriguingly localised, for example the moss Cyclodictyon laetevirens grows nowhere in England except in one Cornish sea cave. Myurium hochstetteri is found in the Azores, Madeira and Tenerife plus the Scottish Hebrides. Others have adapted to extreme or unexpected environments, such as the Splachnum mosses that grow on animal dung and old bones and use flies to distribute their spores. Aulacomnium turgidum was discovered to be re-growing after being entombed in a Canadian glacier for 400 years, and it is claimed that Syntrichia could survive on Mars.

All these interesting facts plus the beautiful illustrations, ranging from photos of bryophytes in their natural environment to close-ups of spore capsules and highly magnified images of leaves (I would have liked scale bars on the micrographs) certainly inspire me to get out and see what I can find. Mosses, Liverworts, & Hornworts of the World succeeds in making the slightly daunting field of bryology more accessible and increasing my appreciation for these ancient, unassuming plants and their importance in woodland ecosystems.